August, 2020

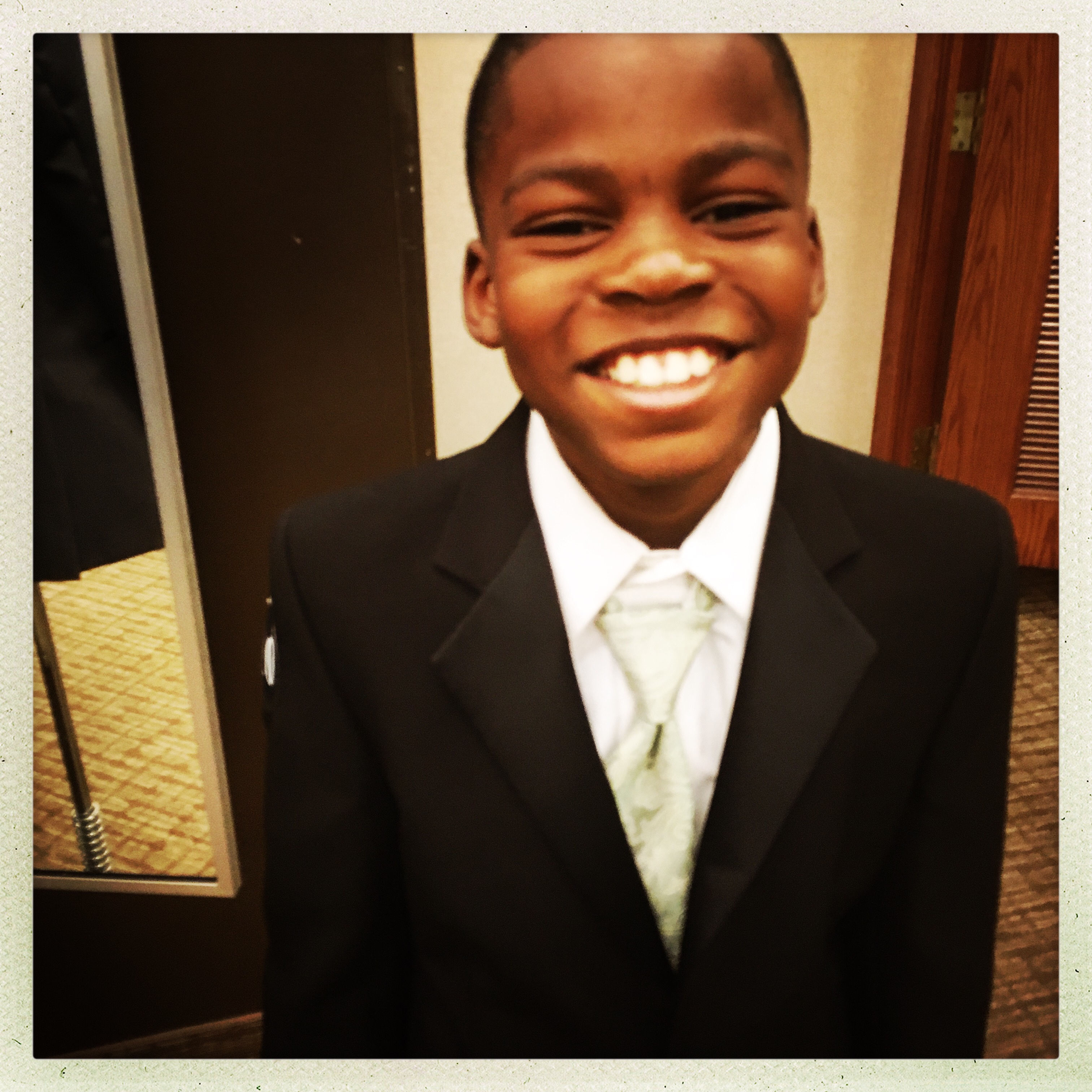

I love William … still. His laugh that fills a room, his smile that tickles your toes. He gives these full body hugs, cradling the back of my head, then kisses me and says, “I love you so much.”

He still wants to sit on my lap, all 4 feet 9 of him with his size 7 shoes. But at 10 years old the world is loving him less, and he is taking notes. He sees what this world does to Black bodies. He’s been to the site of George Floyd’s killing. He saw the list of the dead in bold letters on the sidewalk. He understands his mortality.

“I don’t want to be an adult,” he tells me.

I sit back and let those words sink in. He’s figured it out. That to be like him, to look like him, to be full-grown could spell death. The transition has happened. It took place without my knowing. I, in the swirl of an adult’s daily life, did not see the mask he was putting on. As my baby became a boy, he could see the facial expressions and the body language of others shift. The assumptions of wrongdoings at school. The seeing and unseeing of him.

At school, when there was still school, he would huddle with friends who mirror his reflection. They would trade not only in basketball stories and bad jokes but in lifesaving strategies to keep them safe from the boys in blue. William would make choices not to join white friends in their mischief, knowing that mischief could be deadly for him. His light was dimmed, while I wasn’t watching.

This year he turned 10 and I turned 50 and the world was turned upside down. From school to home he’s been full of anger, stress and frustration. He’s a beautiful mess. It’s being 10, it’s this moment, and it’s his Blackness catching up to him.

These past few months have been illuminating. This is the gift of having a son who can freely articulate his feelings. He opens the window to his world, and I lean in and wait for the breeze.

He says he pretends to be happy because that’s what he knows people want to see. He says he changes the pitch of his voice, so people don’t think he sounds angry. Police scare him. He knows there are good ones … it’s just how can you tell the difference? He says he’s angry all the time and doesn’t know why or what to do.

The light is not gone. William loves fiercely. He still runs and bikes around our neighborhood, carefree and unafraid, the wind in his face. Neighbors still greet him, some with love.

But the world has come for him. You can see it in the slump of his shoulders.

I knew this was inevitable, but I still cry and feel helpless. How do I make this OK? How do I fix it? Then I take a deep breath and realize that I can only do what I have been doing. Love him fiercely. Tell him what I know to be true. Give him space to be emotional, to be angry. Listen and love him again.

If only I can get him through this moment … what a beautiful, caring human being he will be. He was made to make this world a better place. He just needs to survive us.